Fighting Fear and Stigma with Accurate Ebola Information

In July 2015, three months after the last person who had succumbed to the dreadful Ebola virus was buried, Liberians woke to the news that a 17-year old young man had died of the virus. Liberia was no longer considered Ebola-free.

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s words, “The only thing to fear is fear itself” have stayed with me since the first news stories broke about the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, quickly followed by stories of chaos and fear. As someone who has worked with and in the media, I also know that lack of accurate information is a big driver of fear and trauma, which in turn can easily translate into stigma and a withholding of sympathy for those affected by the traumatic events, driven by a compulsion to exclude them as “other.”

It’s been well documented that the Ebola crisis was in large part driven by misinformation in the early days of the outbreak. Rumors spread quickly, and massive blasts of communication, which although aimed at helping people understand the disease and how to deal with it, often ended up being contradictory and just plain confusing. Everyone knew that accurate Ebola information was critical. However, what was missed in the scramble to communicate, was listening to the people affected by the crisis. Simply booming messages at people affected by a crisis is bound to fail.

Internews, a specialized partner of the Health Communication Capacity Collaborative (HC3), found more than “300 types of social mobilization and messaging systems in the three worst-affected countries: Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone.” As the organization’s Senior Director for Global Initiatives Alison Campbell described it: A “chaotic information landscape [that] consisted mainly of information ‘out’ with little opportunity for community dialogue.”

Internews has vast experience working in humanitarian disasters, so it was a natural fit to partner with HC3 already working in Liberia, to widen the approach to getting lifesaving messages to people knowing full well that in rapid onset epidemics, rumors can kill. Who better to target than local journalists deeply connected with their own communities? Whichever way you look at it, individuals need to know the facts and the science behind the disease they’re covering in the media. Working with Liberian journalists was therefore key to Internews’ approach to ensure people had access not only to a wide range of information from trusted sources, but also to channels for questioning and discussing that information.

Alison summarized five takeaways earlier this year in an article that she thought the international development community should take to heart.

- Form genuine partnerships with local media.

- Build capacity rather than paying to disseminate prepared messages.

- Deliver consistent messages and don’t oversimplify.

- Encourage two-way communication with community audiences.

- Help local media realize their full potential as a platform for accountability.

Internews’ health journalism advisor, Ida Jooste recently visited HC3 in Liberia. She spoke to me about how working with journalists can address the stigma related to Ebola. She also shared some insights into Internews’ partnership with HC3, which showed that the commitment and community engagement has been sustained, despite the assumption that there may be Ebola fatigue or messaging fatigue. Community radio journalists have continued to be actively involved in Ebola-related programming in a way that shows “they care and are deeply committed to their communities,” Ida noted. “By investing in groups and journalists who had already proactively taken leadership in the Ebola response, the HC3/Internews team merely added a multiplier effect.”

IDA: Internews in Liberia provides training and follow-up mentoring to a select group of journalists, including from counties most affected by Ebola. These five-day training workshops provide journalists with resources and discussion points of the Ebola-related issues that dominate the news agenda in Liberia. Apart from the obvious joy of the country having been declared “Ebola free” by the WHO on 9 May, the most pertinent discussions relate to:

- The fact that neighbouring countries still have Ebola cases; and

- Stigma against survivors and survivors’ integration into society.

In the week of 25 May, Internews held a weeklong workshop with main theme: Mental health and Ebola. The group was addressed by Dr. Janice Cooper, The Carter Center’s Country Representative, who leads the Center’s Liberia Mental Health Initiative. In the Ebola crisis, she is bringing her expertise in mental health issues to promote an understanding of depression and of the negative effects related to the “othering” of Ebola survivors. Dr. Cooper explained mental health issues themselves are stigmatized. Traditional beliefs hold that mental health-related issues are a curse or punishment from God. When Ebola survivors show signs of depression (most do), they and their surrounding community first need to understand the biological and mental processes behind depression and anxiety. Through adapting existing mental health approaches, she and her teams are helping survivors by teaching coping mechanisms. The Carter Center’s work also extends to creating acceptance and a supportive environment. Dr. Cooper gave an outline of her work to journalists, and introduced them to an Ebola survivor, who answered journalists’ questions about how they are feeling and how they are being treated.

Survivors typically experience self-stigma, guilt (because they survived and others didn’t or because they may have infected others); they are fearful of the recurrence of disease; they re-live the dread of having been so ill and of losing loved ones and they also may still be severely ill and fear that ongoing symptoms will not disappear or get worse. They are widely stigmatized, because some believe they must be bewitched or “the walking dead”, because they managed to survive a disease — around which the initial messaging had been “Ebola kills”! All of this information and accounts of these experiences were passed on to the journalists, who are planning to use the material in their radio talk shows, or radio, TV and print feature stories.

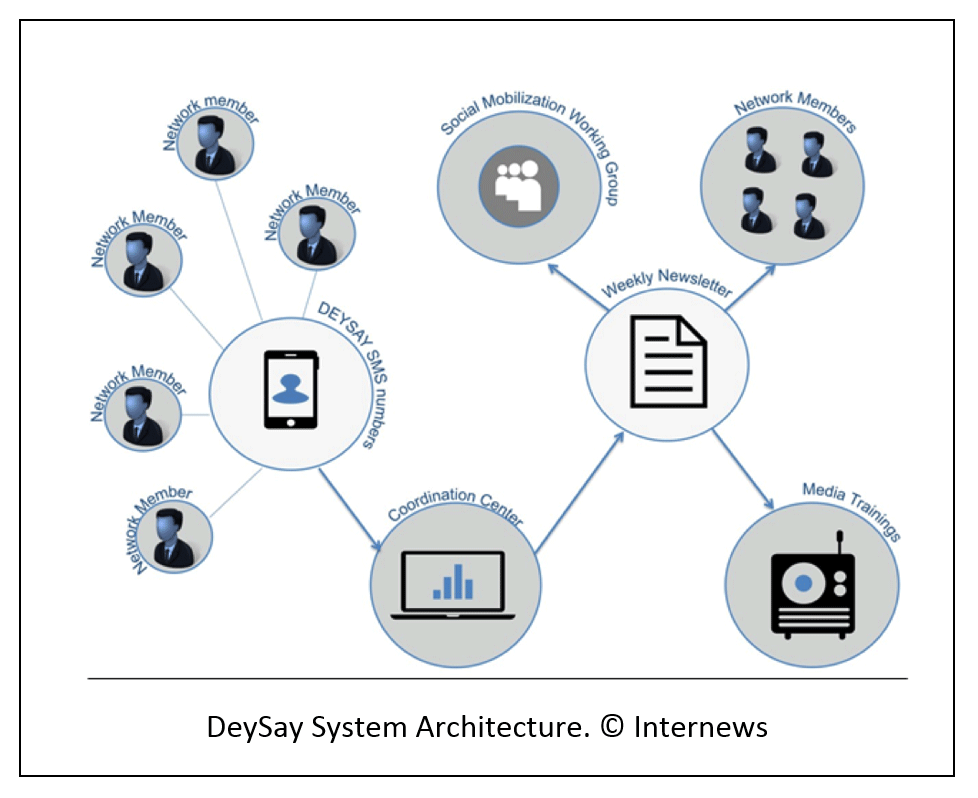

Internews also developed a Rumor Tracker (DeySay – a reference to how people speak about rumors in Liberia), which responds to rumors and debunks myths picked up through the extensive rumor tracking system. These (rumors and factual corrections) are then disseminated to partners through a humanitarian info newsletter, intended for dissemination amongst those who communicate with communities. “DeySay” uses dedicated outreach workers from local partner organizations, as well as local journalists who report rumors through SMS messages to a hotline, where these rumors are categorized by topic and regional scope. Sources include Facebook groups, hashtags on Twitter, influential bloggers, and local media including those from the diaspora, mapping online conversations and triangulating with SMS information from outreach workers. The Rumor Tracker’s information is then fed back to the community of social mobilizers, local media, public officials, and faith-based organizations, as well as to the international humanitarian community in a weekly newsletter that highlights trending issues by community or area. It identifies the most prevalent rumors, provides insights into local and social media coverage, and provides recommendations for addressing the information gaps identified.

Callie: How did this link to HC3’s social and behavior change communication campaign/messages?

IDA: HC3 has been responsive to the issue of most concern in Liberia, stigma against survivors and produced a comic book that communicates messages which helps integrate survivors into communities through normalizing behaviors. Internews distributes these comic books to trainee journalists as a resource. Billboards with the message, “Everyone is a survivor” are commonly seen in Monrovia and in counties. By aligning journalism training with the emerging issues in the country and the issues HC3 has identified as pertinent for its communications strategy, Internews training is responsive to the current information needs in the country.

Callie: How big a problem is stigma?

IDA: The survivors we spoke to, as well as those working in the mental health and counselling field, say it is a really huge problem. Apart from the stigma issues highlighted above, survivors also face the stigma of poverty. In many cases, harvests could not take place because of Ebola. All “Ebola households” were destroyed, meaning sick people and their families lost everything they owned. The belief that survivors benefitted with huge cash payouts does not help their plight. These are all issues that communicators and journalists are working to address.

When you take these factors into account, it is clear why combatting stigma is such an important aspect of Internews’ and HC3’s overall response. More than working to change behavior related to the frightening disease, what needed to happen was to work with communities to tackle the fear and associated stigma that cast such a deadly pall.

For other Internews-related work in Liberia using radio to stem an epidemic, click here.