Rebuilding Trust in a Place “Worse than War”

Anna Helland, far right, in the HC3 Monrovia field office with Marietta Yekeh (center) and Teah Doegmah (left)

As soon as I arrived in Monrovia – actually before I even arrived, as I flew in from Brussels on a near empty plane – I was forced to face the emotional effects of the Ebola outbreak, greeted by airport officials wearing gloves and masks, washing my hands in bleach water for the first of many times, and agreeing to have my temperature taken, also for the first but not last time.

As we drove to town from the airport, traveling in a vehicle that smelled of the bleach water sprayed for my benefit and passing two of Monrovia’s at-capacity Ebola Treatment Units, I asked my driver if this felt like a war. Was it bringing memories of the war back to people? The war is still so close to the surface in Liberia, with many of my conversations with Liberians eventually moving towards the sharing of tales, both funny and tragic, of the many years of civil strife.

I certainly felt as if I had entered a state of emergency and was afraid this would bring stressful memories of the war bubbling up to the surface. It felt to me like war. How my driver responded surprised me: he said it was worse than war. “At least during the war, you knew who had a gun. With Ebola, it could be your brother who infects you without knowing.”

It’s this not knowing – in the community, at the health facility, even within a family- that is bringing about changes in behaviors and social norms that highlight an underlying emotional context, one of unease and distrust.

A new normal seems to be developing and at its base is this feeling of distrust. In previous trips, I hadn’t quite mastered the Liberian handshake, which requires multiple changes in hand positions and ends with a snap (The snap is what’s still giving me trouble). As through much of the continent, a handshake begins all new social interactions, leading to queries on the family and the previous night’s sleep and thanks to God for bringing us to a new day. But touching is no longer allowed, and the strain this causes in social situations is clear as those talking keep their hands in their pockets or their arms crossed to prevent the temptation to put out a hand or even casually touch an arm for emphasis during a conversation.

The ever-constant bleach water containers for washing hands and the security guard to take your temperature are also part of the new normal. Taxis are no longer crammed with passengers. Now they are allowed to take only three in the back seat, and even then, people seemed to be trying hard not to touch their fellow passengers, for fear of becoming contaminated.

All of this fosters an environment of distrust, and the feeling permeates through various layers of society.

Health care workers haven’t been too keen on caring for community members, fearing Ebola will come from those entering their clinics.

Community members themselves fear service providers as they’ve heard so many of them have already died of Ebola and wonder if maybe there is something to the rumors circulating that Ebola is actually injected at the treatment centers.

Distrust has bubbled up to the government level as seen in the unfortunate events in West Point in August, where the government attempted to quarantine an area with high numbers of Ebola cases and overcrowded conditions. Many from West Point are angry with the government for this botched response and the subsequent violence. Residents from West Point have been stigmatized outside their community as coming from an Ebola area, much like those coming from Lofa County were stigmatized at the beginning of the epidemic.

And finally, the health system, which had only just begun to improve during this first decade of peace, has failed them all – health care workers and community members alike. When Ebola made its way to Lofa County from Guéckédou in Guinea in the spring, the Liberian health systems – and it can be argued the global community- were caught off guard, without the needed weapons to fight this type of war.

If this is worse than war, as my driver asserts, intense efforts are needed to foster hope and a renewal of trust- between health care workers and their clients, between the government and its people, and even between brothers as families work to keep themselves and their communities Ebola-free. Trust is not only the key to getting ahead of the epidemic, it’s also the key to rebuilding the health systems in Liberia, which are weak but had been getting stronger. Regaining trust means community members and health care workers feeling confident in their relationships with each other and the services provided. It means trusting themselves and each other to identify the solutions that work best for their communities.

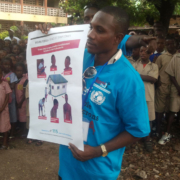

While trust is the solution, social and behavior change communication efforts are the key to fostering this change. These health promotion efforts provide accurate information through strategically crafted messages designed to rebuild trust in the health care system and its workers.

A glimmer of good news from Liberia the last few weeks, with a drop in Ebola cases and more beds available, may help establish trust again. The successes seen in Lofa County, which earlier this year had the highest number of cases in the country, seem to rest squarely with local leadership and community ownership and engagement. Health promotion efforts like ours have encouraged communities to engage by allowing community members to identify their own solutions. This begins to build that trust between them and the healthcare system that promises to provide the best care possible while being sensitive to local customs if care comes too late and a burial is required instead.

Trust allows for these small successes to grow into larger and larger successes and to rebuild what is now a devastated health system. Social and behavior change communication efforts foster the trust to not only getting the outbreak under control but also in leaving systems in place to be better prepared for the next emergency, if and when it comes.

This post originally appeared on the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Ebola website