Ebola is Real: Using Theory to Develop Messaging in a Health Crisis

Question: What is the difference between these two messages?

“Ebola is real! If you get it, you’ll die!”

and

“Ebola is real! If you seek treatment you have a fifty-per-cent chance of recovery?”

Answer: Theory. The Extended Parallel Process Model, or EPPM, to be exact.

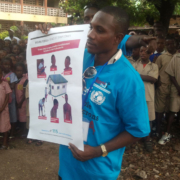

These messages come from a great article in the New Yorker on the use of “culture makers” (i.e. entertainers, community leaders) in Ebola communication. The article describes the experience of a staff member from NGO Search for Common Ground, Mike Jobbins, with Ebola communication in Liberia at the start of the epidemic:

“In Liberia, Jobbins told me, his local colleagues faced an initial wave of government sloganeering that amounted to “Ebola is real—if you get it, you’ll die!” The campaign, he said, sent “a terrible message, especially in a war-affected population where there is already so much fatalism.” The group offered up an alternative, as Jobbins remembers it: “How about, ‘Ebola is real, and if you seek treatment you have a fifty-per-cent chance of recovery?’ ” He added, “You have to hit that sweet spot of treating it seriously enough that people listen and act, but not so seriously that people become fatalistic.”

What Jobbins is describing is the impact of theory on messaging. The first message, “Ebola is real! If you get it, you’ll die!” aims to communicate the real and deadly threat of Ebola. But unfortunately the message doesn’t respond to the fact that when we are confronted with scary, threatening things that we can’t control we tend to put our head in the sand and pretend the threat doesn’t exist. This all-too-human tendency is described by the EPPM. The theory, however, also gives a solution: although we tend to respond to fear of things we can’t control with avoidance, we respond to fear of things we can control with action. This small bit of theoretical understanding clears the way for a new message: “Ebola is real! Seek care and you can survive!”

In the EPPM, the fear is called “threat,” and the belief that one can do something to avoid the threat is called “efficacy.” This Threat/Efficacy relationship is like an equation that must be balanced on either side of an equal sign: the threat we communicate must be balanced by a do-able action the audience can take to avoid the threat. Too little fear with lots of efficacy results in apathy; too much fear with too little efficacy results in avoidance. The sweet spot is symmetry, where just enough fear meets plenty of efficacy and they result in action.

Using theory in health messaging doesn’t have to be a massive undertaking, and you don’t have to be a researcher to do it. What theory does for health communication is provide a road map to your work. It explains what you hope will happen, and why. It gives structure to your thinking, and in the worst of times a little structure and guidance can be very useful to keep you from wandering too far off the path.

Okay, so you can use the Extended Parallel Processing Model for everything, right? It is the only theory you’ll ever need, correct? Well, no. If you try it on another health issue you’ll see why. Take family planning. On the surface, EPPM seems to work – increase the perceived threat of unintended pregnancy, increase perceived ability to use contraception, and you have increased contraceptive use. Except that babies aren’t viruses, and women don’t like thinking of them as threats to be avoided. Instead, women often would rather think of babies as blessings, even when they don’t particularly want to be blessed with a baby right now. That calls for a different theory, one that predicts behavior based on how a woman thinks and feels. Ideation is one such theory – here is a video about how it is used in the promotion of family planning.

So if one theory does not cover all behavior change communication, how do you find out which one will best help you design your intervention? Here are a couple of tools. First is this nice Theory Picker from the CDC. It gives an overview of the major behavior change theories, including:

- Diffusion of Innovation http://www.orau.gov/hsc/theorypicker/doi.html

- Extended Parallel Processing Model http://www.orau.gov/hsc/theorypicker/eppm.html

- Health Belief Model http://www.orau.gov/hsc/theorypicker/hbm.html

- Theory of Reasoned Action http://www.orau.gov/hsc/theorypicker/tpb.html

- Social Learning Theory http://www.orau.gov/hsc/theorypicker/slt.html

- Trans-theoretical Model http://www.orau.gov/hsc/theorypicker/ttm.html

It also can walk you through a series of questions to see which theory might best fit your problem. I tried this with Ebola, and the old “garbage in, garbage out” truism applies. When I tried to answer the questions with just “Ebola prevention” in mind I couldn’t answer questions like: “Many audience members already believe that the consequences of the behavior would be more positive than negative.” But when I thought more specifically of one single behavior (I picked safe burial) the Picker did, indeed, give me the EPPM as one of the top two options to consider. The Picker seems to be a nice tool to explore theory in a really practical way.

For a deeper look at some of the theories and their application, here is a collection of short research briefs. And if the theories of behavior change aren’t enough for you, and you want to get into the theories that guide which media to use to communicate which messages, try this guide on media selection.