Communication Research on SARS and Its Application for Ebola Stigma

Contending with the Ebola outbreak in West Africa has presented an enormous challenge for public health response. However, the decreasing incidence of cases in certain regions of West Africa masks a looming challenge—namely, how do we manage the stigma attached to Ebola survivors as populations recover from this public health crisis?

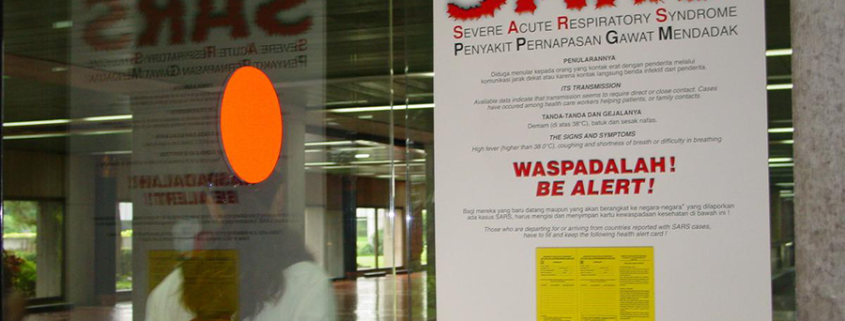

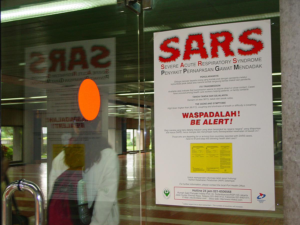

A poster warns travelers about Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) at Soekarno Hatta International airport in Jakarta, Indonesia.

© 2004 Catherine Harbour, Courtesy of Photoshare

During and after an outbreak of emergent infectious disease, fear is itself a contagious agent. Indeed, overcoming psychological contagion is among the most difficult dimensions of public health recovery. The gruesome physical manifestations of Ebola present a perfect recipe for contagious fear, not only among those infected by the disease, but also toward those same individuals should they survive it. This is a painful paradox.

Individuals who survive Ebola develop antibodies that can save the lives of others who are infected. Despite this clinical reality, these antibodies do nothing to protect survivors from long-term ostracism and psychological scars. Prior experience of SARS is illustrative* as it painfully highlighted the power of an emergent infectious disease to stigmatize those who manage to physically recover from it; thus, introducing psychological wounds that can endure long after the infection resolves.

Against this backdrop, health communication efforts can and must play a central role in mitigating stigma toward survivors of Ebola (and other new potential infectious disease outbreaks on the horizon). As communication researcher Peter Sandman has aptly noted, risk perception is the sum of the actual hazard and the outrage (sometimes referred to as ‘dread’ or ‘fear’) accompanying that hazard.

Accordingly, effective risk communication to reduce stigma among Ebola survivors needs to address not only the clinical facts of the disease, but also the sense of dread directed toward those who have been infected by it and who must resume their lives if they’re fortunate enough to have survived. Communication research on SARS has highlighted the importance of health communication campaigns targeted for those at risk of stigma and ostracism, as part of a broader societal-level health communication campaign. Disease survivors at risk of stigma range from members of the general public to health practitioners who may become infected in the course of treating others. Enlisting trusted agents, such as faith-based community leaders, to deliver de-stigmatizing risk messages can aid such vital communication efforts.

Of course, addressing disease-survivor stigma entails recognizing its existence. Ongoing monitoring of traditional and social media content is thus needed to help public health authorities and other risk communication purveyors identify emergence and patterns of stigma at local, national and regional levels. Research can further increase situational awareness of stigma’s prevalence through focus groups, key informant interviews and/or quantitative surveys.

Stigma can have profound economic and quality-of-life impacts on those who experience it and these impacts regrettably can become part of the “new normal” following such outbreaks. In turn, this maladaptive “new normal” can have significant and tragic social justice-related effects on those who have already directly faced the ravages of a terrifying illness. Effective outbreak-related risk communication messaging therefore needs to focus explicitly on de-stigmatizing survivors, to create a constructive new normal without discrimination based on history of illness. In that critical regard, targeted risk communication to reduce stigma toward Ebola survivors can thus help to decrease the very real potential of long-term psychosocial insult on top of physical injury and illness.

*Additional References:

Person et al: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3322940/

Verma et al.: http://www.annals.edu.sg/pdf200412/verma.pdf

Lee et al.: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15913861

Siu: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18503014