Anthropology and Ebola Communication

Health communication has often drawn from the discipline of marketing in conceptualizing how we do what we do, especially when it comes to health issues where people need to use a product or service. Health marketing is concerned primarily with what people do. Another discipline that is increasingly recognized as crucial to the fight against Ebola is anthropology. If marketing is concerned with what people do, anthropology is concerned with why they do it –the “internal logic” of a cultural practice or system.

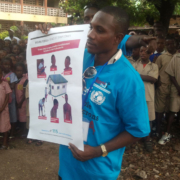

Bong County, Liberia – October 9, 2014: An Ebola response team from the Bong County Ebola treatment unit educates a town in Bong Mines about Ebola. Their ambulance has already collected many people from this town. Several have died, but there has been at least one survivor who has returned. Photo by Morgana Wingard

Anthropology uses a practice called the ethnographic method to understand cultures through interviews and observation. For health communication practitioners based outside target communities, maybe one of the most valuable contributions of anthropology is its role in “translating” between the communities, helping outsiders understand what is going on in a society and what it means to the people who live there. As we’ve seen in this Ebola epidemic, the medical/crisis response/government communities don’t always fully understand the concerns and world view of the impacted communities, or maybe simply don’t appreciate what a profound impact that worldview can have on health workers’ attempts to stop the spread of disease.

Many health communication professionals do use ethnography in their daily work, of course. We conduct or use ethnographies, and work to understand how cultures are put together, and how people in those societies understand themselves, so that we can introduce new ideas or behaviors about health that will prevent illness. Understanding culture has long been standard best practice for communicating about reproductive health, HIV and malaria, to name a few. In a crisis, though, often the thing that is possible to do quickly is the thing that gets done. Ethnography is not quick, or at least it may suffer if it is done quickly (here is a fascinating blog series of whether rapid, “corporate” ethnology done to understand markets is useful). There is evidence that the first phases of the Ebola response did not use an anthropological perspective, and that it is urgently needed now. One simple example from a Washington Post year-end “What Have We Learned About Ebola” article is the color of body bags: in Liberia, white is the color of mourning, and the color of the shroud used to bury bodies. But the body bags used for Ebola victims were black, and people didn’t want their loved ones buried in them. So they started using white body bags, instead. It is this assumption that what doesn’t matter to oneself (the color of a body bag) doesn’t matter to other people that gets us into hot water. We don’t know what we don’t know, but anthropology can help us find out.

To learn more about how culture is influencing the Ebola epidemic, read the articles (listed below) written by anthropologists or with an anthropological perspective. Also, here is a nice overview of what anthropology has helped us learn about Ebola transmission, called Anthropology in the Time of Ebola.) National Public Radio also has an article on “the missing experts,” i.e. anthropologists.

Articles written by anthropologists or with an anthropological perspective:

- Community-Centred Responses to Ebola in Urban Liberia: The View from Below

- Liberia: handling of bodies and national memorials – community perceptions from Monrovia

- Local beliefs and behaviour change for preventing Ebola in Sierra Leone

- Medical Anthropology Study of the Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) Outbreak in Liberia/West Africa

- Mobilising informal health workers for the Ebola response: potential and programme considerations

- Mobilising youth for Ebola education: Sierra Leone and Liberia

- Regional food insecurity, work migration and roadblocks

- Sierra Leone: Gift giving during initial community consultations

- Social Pathways for Ebola Virus Disease in rural Sierra Leone, and some implications for containment, Paul Richards et al

- The flow of money at the community level

- The Opposite of Denial: Social Learning at the Onset of the Ebola Emergency in Liberia

- The significance of death, funerals and the after-life in Ebola-hit Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia: Anthropological insights into infection and social resistance