What Can Be Done to Reduce Stigma and Help Communities Get Beyond Fear

In ancient Greece, slaves and traitors and other undesirables were marked or branded to show their lowly status and allow people to shun them. From that practice we get the word stigma, or mark. Today we use the word to describe the discrimination and social shunning people experience for myriad different reasons – sexual orientation, disease status, weight, ethnicity. As Ebola has spread, so has the stigma associated with the disease. People touched by Ebola – who themselves have it or have had it, who care for people with it, or who come from countries suffering from it – are marked.

In ancient Greece, slaves and traitors and other undesirables were marked or branded to show their lowly status and allow people to shun them. From that practice we get the word stigma, or mark. Today we use the word to describe the discrimination and social shunning people experience for myriad different reasons – sexual orientation, disease status, weight, ethnicity. As Ebola has spread, so has the stigma associated with the disease. People touched by Ebola – who themselves have it or have had it, who care for people with it, or who come from countries suffering from it – are marked.

A few things suggest why stigma has followed Ebola in a way that it hasn’t for, say, influenza, which kills far more people every year all over the globe.

- Novelty. We humans don’t like what we don’t know. We tend to distrust new people, technologies, and diseases more than we distrust known, dangerous, but familiar things.

- Fear. Being afraid can make us act in ways we otherwise wouldn’t, pushing away others in need of care because their disease frightens us so badly.

- Other-ness. When things are frightening and new, it is comforting to be able to say “I can’t get it, because I’m not like her.” It either creates an “Us versus Them” dynamic to create mental separation between those at risk and those not (even if only in the imagination) or it exacerbates existing Us versus Them dynamics with previously stigmatized groups (think injection drug use and homosexuality at the start of the HIV epidemic).

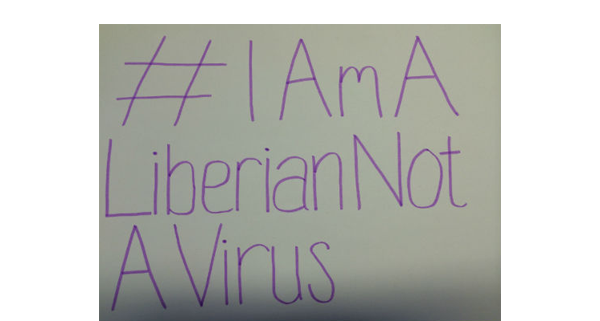

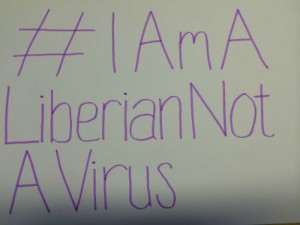

The reaction of many in the US is illustrative of the Novelty/Fear/Other-ness dynamic: – Ebola is frightening, new to the US, and is brought to us from far away by them. Perhaps it should be unsurprising that the family of the Liberian man who died of Ebola in Dallas has experienced stigma and shunning, and that nurses, doctors, journalists, and aid workers of all types coming back from Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea have also been excluded, quarantined, and feared. That Liberians, Sierra Leoneans, Guineans, and Nigerians – and their children – living in the US have experienced shunning and humiliation is appalling. The much more deadly impact of stigma, however, is in the countries where Ebola is epidemic.

Why does stigma matter so much in countries facing epidemics? It is because stigma leads to hiding of the disease, and that leads to further transmission. If people are afraid of a disease not just for itself, but for what people will do to them (or not do for them) if they have it, they are less likely to report symptoms and seek care. Stigma also limits communities’ ability to care for children who are sickened or orphaned by the disease and it prevents communities from welcoming survivors back into the fold. Survivors are potential game-changers in their communities, able to care for people with the virus without falling ill again. It is essential that communities find ways to welcome them home. In Liberia, at least, there is anecdotal evidence that stigma is receding as correct knowledge grows and survivors come home. This article in the Washington Post illustrates both the stigma and the resilience of a community working to care for kids impacted by Ebola.

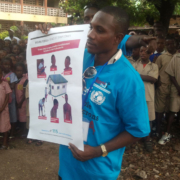

Other health conditions face stigma, too, and we can learn from those experiences. The comparison everyone is making is to HIV/AIDS, of course, but other epidemics may have more relevance. For example cholera, like Ebola, is communicable, deadly, pops up in difficult to extinguish epidemics, and its sufferers and survivors experience stigma. In Haiti, not only the people with cholera experience stigma, but so do the people who are integral to preventing it, the men who clean and maintain latrines. The IRC has developed some key messages and materials to battle stigma and these illustrate the simplicity of the messaging and desired action response: cholera is a disease like any other; help people, but protect yourself; cholera can’t be spread by shaking hands.

From a communication perspective, what can be done to reduce stigma and help communities get beyond their fear to care for their own? What messages and channels should be the focus? Here are some areas for messaging:

- Communicate correct knowledge on transmission and risk (a person who isn’t sick isn’t a risk to me, even if the person has recovered from Ebola)

- Increase people’s sense of self-efficacy for prevention (I know what I can do to protect myself and my family)

- Promote the role of people who have survived Ebola (survivors are assets to my community)

- Care and compassion for children who have lost their care givers (we are all responsible for taking care of the community’s children)

As with any communication, the message you need to convey and the audience you are trying to reach will guide you in figuring out how to communicate. For example, mass media campaign type work can help with correct knowledge, but isn’t very effective for transmitting complicated information; entertainment education can help model change and promote pro-social behavior, but can be time consuming to produce and air; community mobilization can work to organize people to respond, and provides opportunities for dialogue with religious and cultural leaders. All of these channels (each with their strengths and limits) are more powerful when they are used together, because multi-channel interventions extend reach and are mutually reinforcing.