The Sexual Transmission of Ebola: Scicomm as a matter of life and death – Part 2 of 2

*This post originally appeared in PLOS | blogs.

The resurgence of Ebola in Liberia in late June 2015, seven weeks after the country had been declared Ebola free, put a spotlight on how the disease is transmitted, and brought the issue of sexual transmission to the forefront. With this shift away from coping with a national health emergency to dealing with what may now be a “new normal,” different public health messages are required for the people of Liberia.

While new targeted behavior campaigns are being crafted, Liberians will have many questions about when and how Ebola is sexually transmitted. Journalists on the ground will need to find ways to tell that story.

There are helpful linkages to be found in HIV storytelling, but local media will need to address the fact that, unlike HIV-AIDS, the science on sexual transmission risk in Ebola is incomplete.

Ebola is both a sexually transmitted infection (STI) and not one. These stories should not provoke fear, but should communicate the need for safe sex.

“Through viral sequencing we are trying to establish the mode of transmission of the most recent (November) cases. Just as in July, we are also looking to see if it was the same viral strain present in Liberia in 2014”, says Tolbert Nyenswah, the Head of Liberia’s Incident Management System (IMS). “Of course, sexual transmission is a possibility in both cases,” he added.

Nyenswah is a co-author of a New England Journal of Medicine (NEMJ) article titled Molecular Evidence of Sexual Transmission of Ebola Virus, which reports on the examination of semen and vaginal-secretion samples collected from survivors in Liberia in March and April 2015. The case report describes one case of human-to-human EBOV transmission through sexual contact.

A pilot study, also published in the NEMJ, Ebola RNA Persistence in Semen of Ebola Virus Disease Survivors showed Ebola is able to live longer in the testes than previously known. Among the samples, Ebola virus RNA was detected in the semen of 11 of 43 (26%) men 7 to 9 months after the onset of disease. The authors recommend that the risk of sexual transmission of the Ebola virus should be further investigated.

Columbia University epidemiologist Stephen Morse was quoted in a “Popular Science” article,Why testicles are the perfect hiding spot for Ebola saying that he hoped the large numbers (of survivors) will make it easier to figure out when it’s safe for Ebola survivors to return to a normal sex life. “People may want to have children–they may have lost children, and want to go back to normal as soon as possible,” said Morse.

This is one of the questions researchers hope to answer in a National Institutes of Health studyinvolving more than 7,000 people who survived Ebola in Liberia for up to five years as they investigate the long-term health effects of Ebola virus disease. Researchers will seek to determine how survivors can still transmit the virus; also whether those they infect will present with Ebola symptoms and if survivors are at risk for illness in the future.

Though messaging guides during the West African Ebola epidemic all made reference to the possibility of sexual transmission – via bodily fluids – recommendations for changing sexual practices were not a priority for communications during the height of the crisis.

Rania Elessawi, Communications for Development Specialist at UNICEF in Liberia says during the days of the dying all normal human interaction just paused. No kissing, no hugging. What happens in people’s private lives was not even talked about. “Ebola changed the way we loved,” said Elessawi.

The success of the Ebola response, Elessawi says, was that people kept learning as the epidemic unfolded, and kept adjusting and changing the behavior change communications strategy, too.

The epidemic is now at a phase of much less handling and touching of patients and dead bodies in medical settings and at funerals where Ebola virus, present in bodily fluids, had been the primary mode of transmission.

“Now, the focus in behavior change messaging must shift to the realities of sexual transmission”, says Nyenswah of Liberia’s Incident Management System (IMS).

The UNICEF messaging guide for Ebola puts it this way:

Ebola survivors do not have Ebola, but it might be possible that Ebola can spread through doing man and woman business even after testing Ebola free. To make sure Ebola Survivors protect the people they love, they must use a condom correctly every time they do man and woman business. Make sure the survivor throws the used condom into the toilet or burn it.

For now, the WHO (interim) advice on the sexual transmission of the Ebola virus disease includes this guidance:

- Until such time as their semen has twice tested negative for Ebola, survivors should practise good hand and personal hygiene by immediately and thoroughly washing with soap and water after any physical contact with semen, including after masturbation. During this period used condoms should be handled safely, and safely disposed of, so as to prevent contact with seminal fluids.

- All survivors, their partners and families should be shown respect, dignity and compassion.

These two pieces of advice alone indicate the complexity and intimacy of communications and education around Ebola.

Community councillors doing education outreach with Ebola survivors, about combatting stigma. André Smith/Internews

Even with this new emphasis on human-to-human transmission through sexual contact, the question of Ebola’s origins refuses to go away. As before, during the height of the crisis, journalists will need to do their best to answer it.

Communicating the Complex Science of Ebola’s Origins to Shed Light on Human Transmission

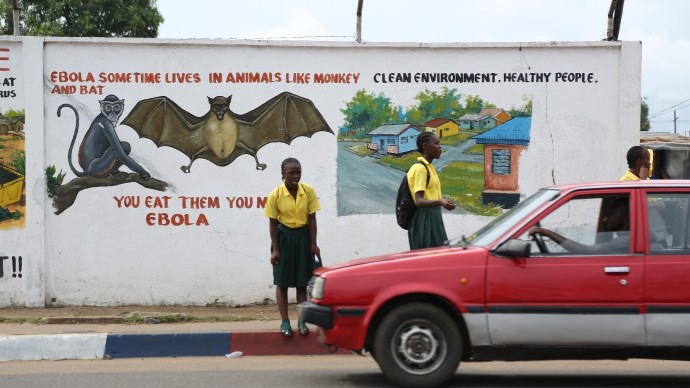

The viral detective story in Liberia (as told in Part 1 of the PLOS post) has helped us understand more about the chain of human to human infections than has ever been known about Ebola, but, for many, the original question: “where does Ebola come from?” remains of concern. In other words, how exactly does zoonotic transmission – the chain of viral transmission from animals to humans – work?

There has been no shortage of attempts to come up with answers.

Karl Johnson, former head of the Viral Special Pathogens Branch at the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC), interviewed for a July 2015 article in National Geographic, said that “despite arduous efforts by some intrepid scientists, Ebola virus has never been tracked to its source in the wild.”

And yet there is a widespread popular assumption – in Africa and elsewhere — that fruit bats were the source for the latest Ebola outbreak.

A 2005 article in Nature, titled “Fruit Bats as Reservoirs of Ebola virus” is the primary source for assertions that the Ebola virus resides in fruit bats, even though the authors made it clear their findings were inconclusive. Robert Swanepoel (now retired) who headed up the Special Pathogens Unit at the National Institute for Communicable Diseases in Johannesburg showed the virus survived in a single spider and in an insect eating bat. But Swanepoel is quick to add that his findings were proof of principle This means the study’s experimental approach – injecting Ebola virus into a range of plant and animal species, then testing if it would take hold – provided a strong signal that bats could be reservoir hosts but it was unable to draw conclusive evidence. The gold standard in science would be to be able to grow the virus in the lab from the viral fragments found in fruit bats.

Screening those samples back at his lab in Johannesburg, Swanepoel found no evidence of Ebola. So he tried an experimental approach, one that seemed almost maniacally thorough. Working in NICD’s high-containment suite—biosafety level 4 (BSL-4), the highest—he personally injected live Ebola virus from the Kikwit outbreak in 1995 into 24 kinds of plants and 19 kinds of animals, ranging from spiders and millipedes to lizards, birds, mice, and bats, and then monitored their condition over time. Though Ebola failed to take hold in most of the organisms, a low level of the virus—which had survived but probably hadn’t replicated—was detected in a single spider, and bats sustained Ebola virus infection for at least 12 days. One of those bats was a fruit bat.

“Journalists have to resist the temptation to oversimplify the complex and to provide answers where only theories exist”, says Jon Cohen, a staff writer for Science. “Pinpointing the origin of emerging diseases is a tricky business. A frightened public logically wants to know where a virus came from to protect people. But all too often, scientists only have clues — in the case of Ebola, bats seem like a logical source, and the first known case played in a tree that harbored bats.”

A WHO Fact sheet describes multiple possible animal sources for the transmission of Ebola to humans:

Ebola is introduced into the human population through close contact with the blood, secretions, organs or other bodily fluids of infected animals such as chimpanzees, gorillas, fruit bats, monkeys, forest antelope and porcupines found ill or dead or in the rainforest.

The Skoll Global Threats Fund hopes to create awareness and solutions around this transmission chain and the fact that “humans and animals increasingly share virulent viruses due to loss of green belts, global warming and poverty, raising the risk of highly disruptive pandemics.”

In simple language: it is widely accepted that there appears to be a link between the threatened habitats of chimpanzees and our shared susceptibility to Ebola. Fruit bats could be agents in spreading the virus from chimpanzee to chimpanzee, to other wildlife populations and perhaps even to humans.

Information Tools for Liberian Journalists

In an attempt to help journalists answer the question “where does Ebola come from?” Internews asked WHO veterinarian and epidemiologist Dr Maarten Hoek to explain this science to a group of environmental journalists in Liberia. He methodically took the journalists through Evolution 101, explained why and how diseases “jump” species and how it happens with greater ease if those species are closely related. He explained how the majority of diseases known to man are zoonoses, i.e. they jump from animals to successfully infect humans, reproduce and then transmit human-to-human. Ancient examples are tape worm, malaria and the common cold. HIV, SARS and MERS are more recent examples, and they jumped from chimps, bats and camels respectively.

One journalist in the Internews training told Hoek plainly: “As an environmental journalist I believe it, but as a person, I don’t. We have always eaten bush meat and bats. The forest has been there and is still there. Where does this Ebola really come from?”

Indeed, the Liberian landscape is lush forest, a sea of green. The valleys and gorges do not appear denuded to the naked eye.

In response to such skepticism, Dr. Hoek pointed to evidence of the decline in the quality and diversity of forest ecosystems. Further, he explains, improved roads and infrastructure are the blessing and curse of development. Whereas a viral infection such as HIV, might have flourished and remained in remote villages, killing all its hosts, our greater connectivity transports both humans and diseases near and far.

A World Bank 2010 report indicates about a third of Liberia’s roads are over-engineered relative to traffic levels. And, the 2014-15 West African Ebola outbreak demonstrated how quickly Ebola could spread once it reached urban centers.

In PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, Kathleen Alexander and colleagues provide a comprehensive outline of the interplay of dynamics that contributed to the Ebola outbreak in an article titled What Factors Might Have Led to the Emergence of Ebola in West Africa? A key dynamic discussed was the spillover of the virus to humans from wildlife – with bats as likely carriers. They also quote evidence that in West Africa, human movement is considered a particular characteristic of the region, with migration rates exceeding movement in the rest of the world by more than seven-fold. Solid science, but it still doesn’t make this story – as it relates to Ebola – easy to tell.

I asked Jon Cohen of Science for advice on how Liberian journalists might tackle these complexities.“Our job is to tell it like it is, nothing more”. Cohen says as long as journalists explain – in simple language – that with Ebola, analysis of the viral genetic material gives it a fingerprint of sorts that links it to Ebola viruses seen earlier in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

“We know that viruses frequently pass from bats to humans, and there are documented cases of Marburg, Ebola’s close relative, likely infecting people who went into caves inhabited by Marburg-infected bats. We also have a documented case of Ebola moving from a dead chimpanzee to a human who handled the animal”.

Where is Ebola going?

Where is our understanding of the virus taking us? In a simple phrase: to more questions, more inquiry. There are more than 13,000 survivors across the three most affected countries in West Africa: Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. Scientists, the journalists who report the science and the communities affected are set to learn much more about the long-lasting effects of Ebola virus disease. And with this comes better insights on how to care for Ebola survivors, who strain from ongoing health problems. Many experience stigma, causing them to live in shame and fear. In an effort to prevent another Ebola crisis, the scientific community is working on developing an Ebola vaccine, of which they are cautiously optimistic, as is evident from current scientific discussion. See alsohttp://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2015/effective-ebola-vaccine/en/

Reporters in West Africa have been learning on the move, whilst living through a most devastating health emergency. Some have been in personal danger; many have been a truth link for their audience, separating gossip from genuine Ebola news. They have had to learn a whole new Ebola science lexicon, and have navigated reportage about issues that span death, dread, confusion, hope and aid politics. It’s too early to say that the dust has settled. But there has been time to think through the stories of the aftermath, to consider how Ebola has exposed the failings in the health system in Liberia and other West African countries – and what needs to be done to address that.

Moses Geply, an Internews trainee journalist in Liberia who is in the Local Voices journalism network, says he and colleagues are ready for this next phase of journalism that makes meaning of what happened in their country.

“This was a first-time health emergency for Liberia, so the mantra was: people won’t understand about this virus, how it spreads, and the medicines used to counteract it”, says Anahi Iacucci of Internews. “But what we learnt here is that really, it is not that difficult to transform a complex matter into something simple, you just really need to work very hard and find the right way to do it.”

Ebola is not over until it’s over. It may never be over. And we are just beginning to learn how to report on Ebola – including answering difficult questions about the origins of this disease.

Now the journalists living and working in Liberia need to make meaning of these new insights for their audiences. Not just the facts, but also what these facts mean – for the sake of their own safety, for their ongoing sense-making of this new and devastating disease.