Where Does Ebola Come From? Communicating Science as a Matter of Life and Death – Part 1 of 2

*This post originally appeared in PLOS | blogs.

When I was in Liberia in June this year, just one month after the country had been declared “Ebola-free,” I noticed how often I heard the phrase “that was before Ebola” or “that was after Ebola”. The Ebola outbreak that began in 2014 brought unspeakable horror to a country still rebuilding after the war. News of new cases in late June 2015 again catapulted the country into high alert. In September 2015, the country was once more declared Ebola-free, but not for long. Ebola’s return in mid-November 2015 has produced yet another high alert.

Thus the realization is growing that it is not “before Ebola” or “after Ebola”, it is during Ebola. Ebola is with us, with the people of West Africa.

August 2014

- Liberia’s President, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf declares a state of national emergency.

- The WHO declares Ebola an “international public health emergency”

May 2015

- Liberia is declared Ebola-free. Liberians heave a collective sigh of relief

July 2015

- A handful of new Ebola cases emerge.

September 2015

- The WHO once again declares Liberia free of Ebola virus transmission in the human population.

November 2015

- Three new cases of Ebola are confirmed. More than 160 people are being monitored for signs of the diseases

Source: http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/history/chronology.html

Before the 2014-25 Ebola outbreak that took 11,000 West African lives and made Ebola a worldwide concern, people in Liberia spoke of an event being “before the war” or “after the war.” Liberians lived through two conflict periods, the First Liberian Civil (1989 – 1996) and the Second Liberian Civil War (1999–2003). “References to before the war and after the war is a heuristic that individuals use to frame or situate the horrors of the war and what it entails. What might be unspeakable”, says Dr. Janice Cooper, who heads up the Carter Center in Monrovia’s mental health program. “It is a reference to which we can collectively relate”.

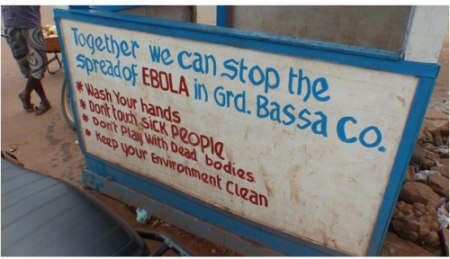

Billboards in Kakata in Margibi County, Liberia, where new Ebola cases were recorded in June and July 2015.

When Ebola re-emerged in Liberia in late June 2015, there were no panicked scenes, no people collapsing in the streets. According to the Dec. 2nd 2015 WHO situation report, a monthly case tracker, the June/July outbreak was confined to six cases. But the euphoria and pride Liberians felt at having defeated the disease was over. In its place, new questions emerged about what it all meant.

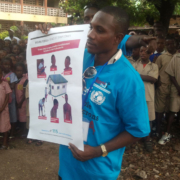

Translating Complexity

At Internews, a media development organization, where I serve as Global Health Media Advisor, we had navigated this complexity alongside local Liberia-based journalists for whom we provide training to help them respond to the Ebola crisis – and who then go on to produce their reports in various media, most often working on a shoestring. We also partnered with the humanitarian community to provide two-way communication channels to affected communities. Early in 2015, Internews set up DeySay, a rumor tracker that detects and manages Ebola-related rumors, which are coordinated and analysed for trends at a central hub in Monrovia. The tracker has picked up on wild speculation that the government of Liberia was profiteering from Ebola and recorded widely held beliefs that the disease is not real. Distrust in government is rooted in the years of civil war and conflict preceding Ebola. Also, early on in the outbreak, many people resisted treatment for Ebola because early presentation of the disease is with symptoms similar to malaria or even flu. Malaria is endemic in Liberia, and so often the (Ebola) symptoms seemed like those of a familiar disease.

“We would analyse the rumor and say: what’s the piece of information that is missing here? Where is the misunderstanding coming from? And then we provide that piece of information to our journalists and social mobilizers and religious leaders on the ground. It’s about really understanding where it’s coming from,” says Anahi Iacucci, Internews Senior Innovation Advisor, who led the Information Saves Lives project in Liberia and deployed DeySay.

In this way, DeySay has been a valuable journalistic tool used by Liberia-based reporters in the Internews training program. As rumors were collected with the DeySay tracker, myths were debunked by providing a factual correction or explanation as illustrated below:

- Rumor from Sinoe County: There are people who are refusing to take their children to the hospital for the Polio and vitamin A immunization campaign because they believe that the government is using the campaign as a way to infect people with Ebola.

- Well-sourced and accurate response: From the 26 nation-wide Polio and vitamin A immunization campaign: Children below the age of 5 were given free drops in the mouth to protect them from the polio virus. The polio immunization campaign was not organized by the government to infect people with the Ebola virus. With the vaccination, young children are protected against the virus, to ensure that Liberia will continue to be polio free.

- Rumor from Nimba County: A woman in Nimba County was arrested after she refused health workers trying to give her child the Polio and vitamin A vaccine. She said the vaccine would infect the child with the Ebola virus.

- Well-sourced and accurate response: A parent has the right to refuse the immunization of his child. No one should be arrested for refusing to take part in the immunization campaign.

Beyond tracking rumors, Internews is also partnered with GeoPoll in a project that traces the most frequently asked questions around Ebola. During all phases of the crisis – during Ebola’s peak in July to October 2014, in the Ebola-free phase as well as after its resurgence in July 2015 – the most enduring question has been: Where does Ebola come from?

The Medical Forensics of Ebola

Like the people of Liberia, scientists have also been asking this question; specifically, where did the new Ebola cases in Liberia come from, in late June, seven weeks after the country had been declared Ebola free, and again, in mid-November, ten weeks after the country had again been declared Ebola free. Although their present focus is on West Africa, the question of where Ebola originated has bedeviled virologists since the virus was first identified in 1976. In time this strain would be dubbed Zaire virus. Subsequently, additional strains of the virus emerged, named for the areas where they occurred. Later in 1976, Sudan virus was identified, a strain of the virus with a lower fatality rate than Zaire virus. Ivory Coast Ebola virus, isolated in 1994, showed slightly different characteristics again. In the period 1989–2007, three additional Ebola subtypes have been identified, Reston virus, Taï Forest virus and Bundibugyo virus. The strain of the virus present in the multiple outbreaks in West Africa since March 2014 is simply called Ebola virus.

So, where did the new cases in June 2015 come from?

A simple headline, released by Liberia’s Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, sums up a complex scientific investigation.

“Ebola virus genomes from latest flare-up rule out introduction from Guinea or Sierra Leone.”

The government’s news release further outlines the players and medical forensics that led to this conclusion:

“A joint team – including the Liberian Institute for Biomedical Research (LIBR), the United States Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) and the Liberian Ministry of Health – has sequenced the EBOV isolated from the index case in this cluster.”

As Tolbert Nyenswah, the Head of Liberia’s Incident Management System (IMS) later explained, “The form of the virus present in June was of a mutation present in Liberia, not neighboring countries. Both sequences are identical and are consistent with this cluster representing a continuation of the EBOV outbreak in Western Africa, as opposed to a separate introduction from a reservoir population.”

Say What?

Through-out the epidemic, viral sequencing had shown different mutations of the current strain found in West Africa, thus enabling scientists to identify the origin of a single infection as being a version circulating in localized parts of Liberia, Sierra Leone or Guinea. This resolution of the Ebola DNA detective story helped put an end to the common rumor that the new Ebola cases came from across the border, from Guinea or Sierra Leone. Or did it? As the science on Ebola has unfolded, those most affected have been trying to make sense of the complex procedures utilized in scientific laboratories to arrive at such conclusions. However, this language is not easy to follow if you’re new to molecular genetics. So, the question local journalists repeatedly faced was How can we make sure this critical information is broadly understood by the people?

“This news is in deep science, not in English,” says Eric Opa Doue, a community radio journalist in the Internews health training program who holds a degree from the Ghana School of Journalism.

“I first need to digest and simplify it, then send it to the translation department at my station, to ensure the message is correctly deciphered in Kru and Bassa languages for my audience, so that everyone will understand. For example, Opa Doue asks, “what does the following sentence (from the Liberian government’s news release) mean – in plain language:

‘The sequence groups closely with previous isolates from Liberia and is distinct from the viruses currently circulating in Sierra Leona and Guinea.’”

Most importantly, local Internews reports focused on the fact that this scientific finding ruled out cross-border transmission from Sierra Leone or Guinea. It also ruled out rumors, including that the boy died from eating infected dog meat. In essence, the message became the fact that this was the same Ebola they’d been dealing with since 2014.

“Ebola Deeply”

Ebola Deeply, an independent global digital media project led by journalists and technologists whose goal is to “build a better user experience of the story by adding context to content,” also took on this challenge. Work such as their two-part series Unlocking Ebola’s Secrets has been helpful to Internews trainees and others following and attempting to explain this story. To produce this report, the Ebola Deeply team visited Liberia’s genome sequencing center where researchers examined the genome of viral samples taken from the 17-year old boy who died in the town of Smell no Taste in Margibi County. There they learned that by using genome sequencing, the scientists were able to determine that the viral strain in the boy’s body was genetically similar to that circulating in this area of Liberia last year. The viral forensics had shown that the virus which killed the 17-year-old young man in June 2015 and which caused Ebola to re-emergence in a small pocket in his town in Margibi County, had the same signature as the virus present in his area earlier in 2015.

As the Ebola Deeply journalists explained in Unlocking Ebola’s Secrets, the process of genome sequencing is like “turning the pages of the virus’s personal diary”.

Learning (More) from Ebola

Toward the end of July 2015, the WHO’s Dr Bruce Aylward and colleagues from the US Centers for Disease Control and the Liberian Ministry of Health told humanitarians responding to the Ebola crisis that the world of science is braced for a period of immense learning. The West African Ebola epidemic has been the most devastating the world has seen. More than 11,000 people have died, and, connected to this scale and to an increasingly more efficient Ebola response, is the fact that this epidemic has left behind the largest number of Ebola survivors ever – people who have been infected, but who did not die of Ebola. To families, these are loved ones who are still with them; to science, this is an opportunity to unravel some of the many questions about Ebola that remain unanswered.

What scientists like Aylward are now saying about Ebola are things that could not have been tackled in the horror and haste of the humanitarian crisis, when the entire focus was about saving lives and preventing transmission to caregivers from those who were dying.

What scientists like Aylward are now saying about Ebola are things that could not have been tackled in the horror and haste of the humanitarian crisis, when the entire focus was about saving lives and preventing transmission to caregivers from those who were dying.

In part two, I discuss what is being learned about new modes of Ebola virus transmission and the public health messages that are being prepared and implemented to communicate the implications for the people of Liberia.