On the Ground in West Africa: Elizabeth Serlemitsos

Everywhere I go in Monrovia, the capital of Liberia, they take my temperature. Eating at a restaurant? There’s someone wielding a thermometer at the door. Headed into a building for a meeting? Same thing. Even when I pull up to park at the apartment building where I am staying, I have to roll down my window so an attendant can hold a thermometer up to my face to make sure I don’t have a fever. A fever is the first sign of Ebola and I am living in the epicenter of the outbreak.

This is just the new normal here. We don’t shake hands when we greet each other. We wash those hands all the time, mostly at washing stations set up by the entrances of every building. There was some hysteria here in the early days of the outbreak, I am told, but shops and restaurants on the streets I walk here in Monrovia are open now and it is business as usual. We are vigilant, but we are calm. It is hard to get Ebola. We know that it’s not casual contact that spreads this horrible disease. It is nurses and doctors who care for the sick who are at risk, relatives who physically comfort those with the disease, those who try to prepare the dead for a proper burial.

I arrived in Liberia on October 10 and plan to be here for as long as it takes to turn things around. By next month we will be a team of six on the ground (three Americans and three Liberians) here with the Johns Hopkins University Center for Communications Programs, funded by USAID to support the Liberian government’s response to the Ebola outbreak. Our work here is to communicate with Liberians about Ebola, quieting rumors and fear and giving them the information they need to help protect themselves and their families from Ebola.

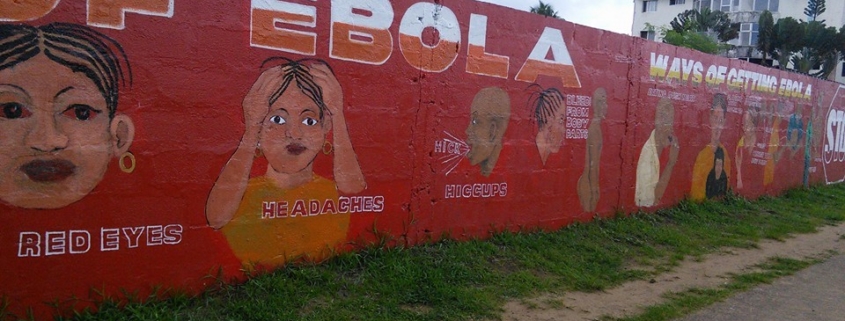

The first message, back in the early days of the epidemic, was that Ebola is real. There were many questions and doubts. Conspiracies were everywhere. That message is now getting through. Now we have moved on to new messages: Practice good hygiene, like regular hand washing. If someone in your house is sick, get help and don’t try to treat him yourself. Keep the sick person isolated. If someone in your house has died, get help and don’t touch her body. We have been helping to strengthen the call center that was set up to provide that help. We think the messages are getting through.

Soon we hope to move to phase three: welcoming survivors back into the community, as the heroes that they are.

When I open my laptop and read headlines from the United States, I find it hard to believe the level of hysteria so many miles away. The risk is so miniscule. Only those who have directly treated patients in the United States have gotten sick and yet people are afraid to travel to Dallas? It makes no sense.

Shortly after I got here, I attended a big WHO briefing and heard a report from Lofa, a county in northern Liberia. The data indicates that things are starting to turn around up there. Strong, motivated leadership coupled with an engaged community look to be making the difference. It’s not the story everywhere. This epidemic is different in different areas. But in an outbreak like this, the bright spots are something to celebrate. Just without the hugs or the high-fives.

*This post originally appeared on the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health website.